Executive summary

We undertook this survey to find out about conditions at small-market newspapers in Canada and to explore the sector’s prospects at a time when newspapers in general face major challenges. The Local News Map, a crowd-sourced platform that tracks changes to local news outlets across the country, has documented the closing of 36 local free and subscription daily newspapers and 195 community papers over the past decade (Lindgren & Corbett, 2018).

The survey is a collaborative effort by The Local News Research Project, led by Ryerson University professor April Lindgren, and the non-profit National NewsMedia Council, a voluntary self-regulatory organization that promotes editorial standards, ethics, and news literacy. Together, we sought answers to questions about workload; the use of digital tools; how employees stay up to date with ethical, technological and other changes; and how publications engage with audiences. Respondents were also asked for their views on the future of the industry, including challenges and opportunities.

A similar exercise was conducted in the United States in 2016 (Radcliffe, Ali & Donald, 2017), so we designed the Canadian survey to allow for a comparison of small-market newspapers in the two countries. To be consistent, we adopted the Americans’ definition of what constitutes a small-market newspaper, that is, a print publication with a daily/weekly circulation below 50,000 copies.

In Canada, 30 of the 90 daily newspapers have a total weekly print circulation below that threshold. Print-only circulation numbers are unavailable for the country’s 1,029 community newspapers (published fewer than four times per week), but 954 have a combined print and digital circulation below 50,000 (Kelly Levson, News Media Canada, personal communication, December 16, 2018). There were 127 eligible responses to the online survey, which was conducted between February 5, 2018, and April 25, 2018. Responses were anonymous.

In addition to asking the same questions included in the American survey, we included supplemental queries related to knowledge of ethics and editorial standards in newsrooms, diversity in staffing, and audience engagement strategies.

The majority (61 per cent) of the feedback received from this survey came from editors and reporters. Most respondents (81 per cent) worked at newspapers with newsrooms staffed by five or fewer editorial employees. Two-thirds worked at weeklies; more than half were employed at papers with a print circulation between 1,000 and 10,000. Almost all of the newspapers rely on advertising as a revenue source.

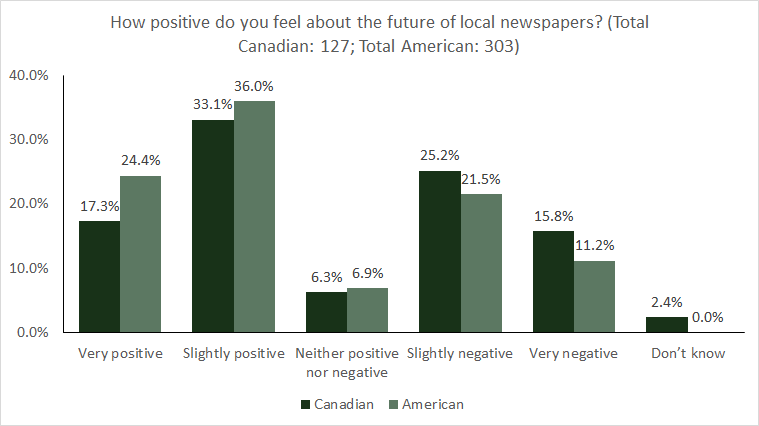

The survey results point to a sector characterized by shrinking newsrooms deeply divided over the future. While 50 per cent of respondents were “very positive” or “slightly positive” about what is in store for the sector, 41 per cent were “slightly negative” or “very negative.” Optimism was much more pronounced among older respondents.

The good news is that the Canadian survey results paint a picture of newspapers that recognize the need to engage with their communities: 43 per cent of respondents said their publication had launched an editorial campaign on an issue that is important to their community, 96 per cent said they had published contributions from community members, and most use Facebook to connect with readers. Respondents were also steadfast in their belief that a trusted local newspaper providing timely, reliable local news has a significant competitive advantage when it comes to competing for advertising and audiences even in these turbulent times.

Respondents defied stereotypes of smaller newsrooms as reluctant to embrace digital tools: Most have embraced some aspect of “digital.” Three quarters said they actively post to their organizations’ Facebook account and more than half contribute to their newspapers’ Twitter feed. Three quarters reported using some sort of metrics to measure audience engagement with their content.

The responses to our survey questions, however, also highlighted significant challenges facing the sector. Survey participants said their efforts are constantly undermined by the perception that their industry is on its deathbed—a perception that harms their ability to attract new audiences, advertisers, and young journalists. The responses also pointed to other issues, outlined below.

- Smaller newsrooms: Fifty-seven per cent of respondents said there are fewer people in their newsrooms now than in 2016. Multiple survey participants linked waves of layoffs to concerns about the quality of journalism in their newspapers.

- A work culture that is demanding more of its workforce: About one third of journalists said they are producing more stories and working longer hours compared to two years ago. Forty per cent of respondents reported that they regularly work more than 50 hours per week.

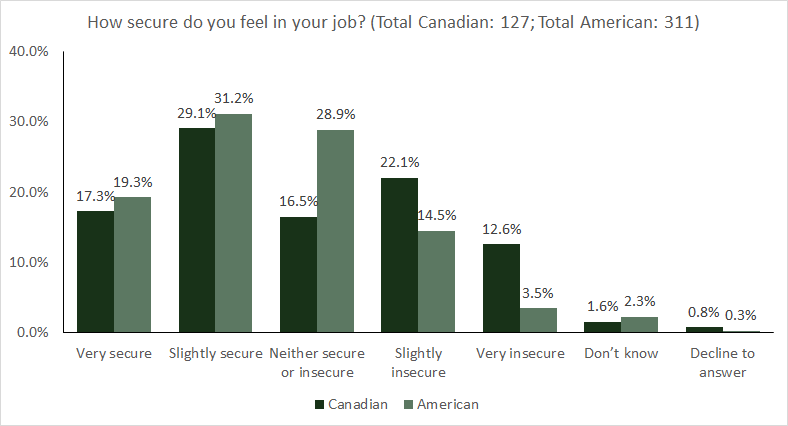

- A split between employees who feel secure in their jobs and others who are concerned about job security: About one-third of respondents (35 per cent) said they felt slightly or very insecure in their positions while nearly half (46 per cent) said they felt very secure or slightly secure.

- Limited technology training/investment in newsroom personnel: Respondents are learning about new technology and tools related to the industry mostly on their own—only 20 per cent said their employers paid for training courses.

- Limited employer-sponsored ethics training: Most respondents said they learn about journalism ethics and best practices on the job from fellow journalists and from published articles. Only about one third (32 per cent) cited employer-sponsored resource guides or ethics training courses.

- Difficulties attracting and retaining qualified staff.

- Intense competition from non-local digital platforms and publications for audiences and advertisers.

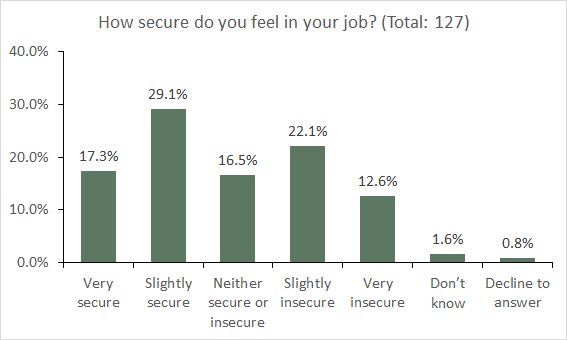

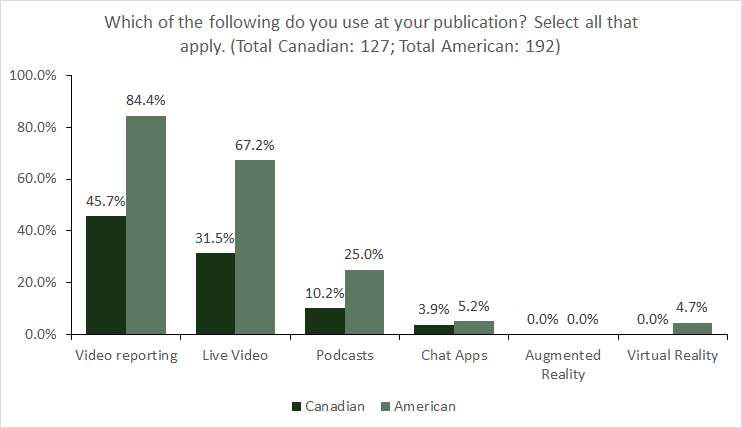

While Canadian and American small-market newspaper sectors are dramatically different in terms of scale, the pool of self-selected survey respondents in both countries turned out to be remarkably similar. Responses to the 23 common questions revealed two notable differences between the two countries. In the first instance, we found that respondents’ use of video reporting, live video and podcasts in the United States was approximately double that of Canadian respondents. The second significant difference had to do with sentiments about the future. Canadians were generally more pessimistic in their outlook. While approximately half of the participants in both surveys felt slightly or very secure in their jobs, more than one third (35 per cent) of the Canadians felt slightly or very insecure in their jobs compared to just 18 per cent of American respondents.

The report concludes with recommendations related to revenue diversification, newsroom collaborations and relationship building with audiences. Given their almost complete reliance upon advertising revenue, for instance, we point to the need for publications to develop supplementary revenue streams. We recommend building relationships with journalism schools to attract new talent, diversify newsroom staff and to publicly demonstrate confidence in the sector’s future. Newsroom collaborations are highlighted as a way to bolster limited training resources and produce quality journalism. And where it isn’t already the practice, we suggest publications make it a priority to adopt and publicize a code of ethics as a way to build trust with readers.

![localnewsresearch_may24_final[2]URL](https://portal.journalism.torontomu.ca/goodnewsbadnews/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2019/02/localnewsresearch_may24_final2URL.png)

Good news, bad news: A snapshot of conditions at small-market newspapers in Canada by April Lindgren, Brent Jolly, Cara Sabatini and Christina Wong is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at http://portal.journalism.torontomu.ca/goodnewsbadnews/

Introduction

We set out with this survey to find out about conditions at small-market newspapers in Canada and to explore the sector’s prospects at a time when newspapers in general face major challenges. The survey, which was in the field from February 5, 2018, to April 25, 2018, is a joint initiative by the Local News Research Project run by Ryerson University journalism professor April Lindgren, and the non-profit National NewsMedia Council, a voluntary self-regulatory organization that promotes editorial standards and news literacy. Together, we sought answers to questions about workload; the use of digital tools; how employees stay up to date with ethical, technological and other changes; and how publications engage with audiences. Respondents were also asked for their views on the future and industry challenges and opportunities.

While the strategies, outlook and working conditions at larger Canadian newspapers are subject to regular scrutiny (Goldfinger, 2017; Popplewell, 2018; Watson, 2017), much less is known about the state of small-market publications. Indeed, journalism scholars have called for a “more nuanced vocabulary to speak about newspapers and local news. Grouping all newspapers into a monolithic industry – as general sector analyses often do – suggests a homogenous experience” (Ali, Schmidt, Radcliffe & Donald, 2018, p. 2).

The idea for this survey originated from discussions at Is no local news bad news? Local Journalism and its Future, a June 2017 conference hosted by the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre. Attendees at the Toronto conference included Damian Radcliffe, a professor of journalism at the University of Oregon and co-author, with the University of Virginia’s Christopher Ali, of Life at Small-Market newspapers: Results from a survey of small-market newsrooms (Radcliffe, Ali & Donald, 2017). This U.S. survey, conducted along with a series of in-depth interviews with industry experts and journalism practitioners (Ali, Schmidt, Radcliffe & Donald, 2018; Ali, Radcliffe, Schmidt & Donald, 2018), sought to gather more information about the reality of working at smaller newspapers, which its authors defined as publications that have a daily/weekly print circulation below 50,000. Of the 7,071 newspapers published in the United States in late 2016 when the survey was conducted, 6,851 fit the definition of a small-market newspaper, constituting what the survey authors described as a “silent majority we know little about” (Ali, Schmidt, Radcliffe & Donald, 2018, p. 2). There were 420 eligible responses to the U.S. questionnaire.

By adopting the same definition of a small-market newspaper and asking the same questions, the Canadian survey produced data that can be compared to the American results. In Canada, 30 of the country’s 90 daily papers have a total weekly print circulation below 50,000. Print-only circulation numbers are unavailable for the country’s 1,029 community newspapers (published fewer than four times per week), but 954 have a combined print and digital circulation below 50,000 (Kelly Levson, News Media Canada, personal communication, December 16, 2018).

In addition to posing the same questions as our American counterparts, we also asked about newsroom ethics, diversity and staffing and included more specific queries about audience engagement strategies. There were 127 eligible responses to the Canadian survey.

Our primary motivation in conducting this research was to better understand the reality of working at a small-market Canadian newspaper and the sector’s prospects at a time of major disruption. In June 2018, Postmedia Network Canada announced another round of layoffs and buyouts, the closing of six newspapers in Ontario and Alberta, and the cancellation of the print edition of three other publications (Shufelt, 2018). A deal in late 2017 between Postmedia and Torstar Corp. saw the two corporations exchange a total of 41 newspapers and then close three dozen of them (Krashinsky Robertson, 2017).

More generally, the Local News Map, a crowd-sourced platform that tracks changes to local news outlets across the country, has documented the closing of 36 local free and subscription daily newspapers and 195 community papers over the past decade (Lindgren & Corbett, 2018).

The losses continue to mount even as Canadians insist they value newspapers as important actors in democratic societies. A recent Vividata survey found that while only about one-third of respondents turned to newspapers in the previous week for news, considerably more saw them as trusted sources: 66 per cent rated the print editions of local newspapers among their most trusted news sources while 70 per cent placed their highest trust in the print edition of national dailies (Vividata, 2018).

Anecdotal evidence also suggests newspapers have a special place in Canadians’ news diets. Local mayors, for instance, fretted about how to keep their electors informed in the aftermath of the 2017 Postmedia/Torstar deal (Watson, 2018). Residents in Guelph, Ontario, shed tears and thanked reporters when they gathered outside the Guelph Mercury’s building the night before the local daily published its final edition on January 29, 2017 (Bala, 2017; CBC News, 2016). Most obviously, however, the evidence that smaller newspapers matter is evident in the journalism they publish. The list of nominated and award-winning stories includes investigations of everything from the living conditions of marginalized citizens dealing with slum conditions (Schliesmann, 2016) to local officials’ handling of development and land deals (The Voice, 2018).

Why focus on small-market newspapers?

Newspapers have been—and continue to be—significant contributors to vibrant, well-functioning local democracies. They play a role in fulfilling what researchers have identified as the critical information needs of communities, including the need for timely, reliable information about risks and emergencies, health, education, transportation, economic opportunities, the environment and civic and political issues (Friedland, Napoli, Ognyaova, Weil & Wilson III, 2012). A recent Scientific American report offered a concrete illustration of why local health news, for instance, makes that list: It quoted epidemiologists who are worried that the closing of so many local newspapers in the United States means they are losing an important early warning system for the outbreak and spread of infectious diseases (Branswell, 2018).

More generally, a study of local political reporting in Danish newspapers concluded that although newspapers are no longer the direct source of news for the majority of citizens, they still punch above their weight in terms of their impact on the local news environment. They are often the only source of day-to-day public affairs coverage, they cover political stories ignored by other media, and in many cases their journalism still sets the agenda and informs the reporting of other news organizations (Nielson, 2015).

Newspapers also play a role in constructing a shared a sense of community and place. Benedict Anderson (1991) argued that they are integral to the building of nations, which he characterized as “imagined” political communities: “…imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion” (p. 6). The same dynamic, some scholars have suggested, plays out at the local level in that citizens become acquainted with issues and community norms through “the simultaneous consumption or ‘imagining’ of the stories in local newspapers” (Paek, Yoon & Shah, 2005, p. 590). Others have delved more deeply into the role of small newspapers as community builders, suggesting that the coverage they generate is a form of “mediated social capital” that brings ordinary people together and links them to those in power (Hess, 2015).

Studies have linked newspaper readership to civic engagement, including membership in community organizations and participation in community leisure activities (Jeffres, Lee, Neuendorf & Atkin, 2007). The closing of daily newspapers in Seattle and Denver has been associated with a decline in civic engagement as measured by factors such as participation in or leadership of a community group or organization (Shaker, 2014). An earlier study that examined what happened when the Cincinnati Post shut down at the end of 2007 suggested the short-term effects included fewer candidates running for office in areas that were Post strongholds, an increased chance that incumbents would be re-elected, and declines in voter turnout and campaign spending (Schulhofer-Wohl & Garrido, 2011). More recent research has linked the closing of local newspapers to an increase in U.S. political polarization (Darr, Hitt & Dunaway, 2018).

Reporting by newspapers has also been associated with the performance of public institutions. The decline in government corruption in the United States during the Gilded Age of the late 19th and early 20th century, researchers have suggested, coincided with the emergence of independent, less partisan newspapers (Gentzkow, Glaeser & Goldin, 2004). More recent American research that tracked changes to local news outlets between 1996 and 2015 linked the closing of local newspapers to higher government borrowing costs that occurred in the absence of media scrutiny of school, hospital and other infrastructure projects (Capps, 2018).

Understanding what is happening in newsrooms of local newspapers is also important because their contributions aren’t always positive: Newspapers have been implicated in the negative stereotyping of neighbourhoods (Lindgren, 2009). Their coverage often excludes individuals and groups, particularity minority groups (Hess, 2015), and they have been shown to under represent and misrepresent diversity and racialized groups (Lindgren, 2011; 2013).

Finally, delving into what is happening to newspapers is about gaining a better understanding of whether newspaper journalists, many of them reeling from multiple rounds of newsroom layoffs, can still do their jobs. A recent U.S. study that identified the net loss of 1,800 local publications in that country since 2004 pointed to a growing number of “ghost” newspapers, where “the editorial mission and staffing have been so significantly diminished that their newsrooms are either nonexistent or lack the resources to adequately cover their communities” (Abernathy, 2018, p. 8).

The Canadian context

Research that explores what is happening to Canadian newspapers and the impact of disruption is relatively limited. It is clear, however, that the challenges facing the sector are significant. Newspaper revenues collapsed to $2.6 billion in 2017 from a high of $4.7 billion in 2008 (Winseck, 2018). The overall percentage of Canadians who rely upon print sources for news continues to decline: it dropped to 31 per cent in 2018 from 36 per cent two years earlier (Newman, Fletcher, Kalogeropoulos, Levy & Nielsen, 2018). Only 22 per cent of Canadians have print or digital newspaper subscriptions (Earnscliffe Strategy Group, 2017, p. 7) and in a mid-2017 survey, 86 per cent of respondents said they will still get the news they need if their local daily newspaper goes out of business. Even respondents who lived in one-newspaper towns were blasé: 84 per cent said they will still stay informed if the local newspaper ceases to exist. The results were consistent across regions, age groups, gender, political affiliation, urban and rural respondents, and homeowners and renters. “Because people consume information using a variety of digital platforms,” the pollsters noted, “they may not be as aware as used to be the case of the sources of their news, and the important role of local newspapers in newsgathering. It’s also possible that they believe that different media outlets will fill in the gaps…” (Anderson & Coletto, 2017).

Data from the Local News Map, a crowd-sourced tool that tracks changes to local news media across Canada, shows that 262 local news outlets have closed since 2008 including 231 newspapers in 180 communities. Thirty-six were dailies and 195 were community papers that published fewer than five times per week (Table 1). By comparison, only 40 newspapers launched over the same decade (Table 2).

Table 1. Breakdown of closings by type of media, January 1, 2008 to December 1, 2018.

| Type of media outlet | # of closings |

|---|---|

| community paper | 195 |

| daily paper - free | 23 |

| daily paper - paid | 13 |

| online | 13 |

| radio - private | 2 |

| radio - public | 6 |

| TV - private | 10 |

| TV - public | 0 |

Source: Lindgren & Corbett, 2018

Table 2. Breakdown of newly launched outlets by type of media, January 1, 2008 to December 1, 2018.

| Type of media outlet | # of launches |

|---|---|

| community paper | 39 |

| daily paper - free | 1 |

| online | 46 |

| radio - private | 6 |

| radio - public | 3 |

| TV - private | 3 |

| TV - public | 5 |

Source: Lindgren & Corbett, 2018.

Content analyses suggest these newspaper losses have affected the availability of news. A Public Policy Forum study that examined the newspaper content in 20 different communities found that the total number of articles declined by nearly half between 2008 and 2017. Over that same period, coverage of democratic institutions and civic affairs fell by more than one third (Public Policy Forum, 2018).

Critics suggest corporate concentration is intimately linked to declines in both the quality and quantity of news coverage in local newspapers. Marc Edge (2018) argues that Canada’s federal competition bureau has failed to apply antitrust laws to newspaper mergers and takeovers—business deals that sounded the death knell for many smaller publications and led to domination of the sector by a few large players (see Table 3 and Table 4)

Table 3. Ten largest community newspaper chains in Canada as of December, 2018.

| Top 10 community newspaper owners | # of titles |

|---|---|

| Postmedia Network Inc. | 86 |

| Black Press Ltd. | 85 |

| Metroland Media Group | 78 |

| snapd Inc. | 72 |

| Glacier Media Inc. | 44 |

| SaltWire Network | 25 |

| TransMet Logistics/Metropolitan Media | 25 |

| TC Media | 21 |

| Icimédias inc. | 20 |

| Brunswick News Inc. | 19 |

Table 4. Daily newspaper ownership in Canada as of November, 2018.

| Owner | # of titles |

|---|---|

| Postmedia Network Inc./Sun Media | 35 |

| TorStar Corp. | 12 |

| SaltWire Network Inc. | 8 |

| Groupe Capitales Médias | 6 |

| ALTA Newspaper Group/Glacier | 3 |

| Black Press | 3 |

| Brunswick News Inc. | 3 |

| Continental Newspapers Canada Ltd. | 3 |

| Quebecor | 3 |

| F.P. Canadian Newspapers LP | 2 |

| Glacier Media | 2 |

| Globe and Mail Inc. | 1 |

| Power Corp. of Canada | 1 |

| TransMet | 1 |

| Independent Titles | 7 |

| Total | 90 |

Source: News Media Canada, 2018a.

Data from the Local News Map show that the large newspaper chains account for most of the newspaper closings (all types of newspapers) and relatively few new titles since 2008 (Table 5 and Table 6). Critics argue that these losses are the result of corporate ownership models that have little or no connection to local newspapers or the communities where they operate. In the extreme case of private equity and hedge fund ownership, these critics say, no effort is made to balance business interests with civic responsibility and the primary allegiance is to earnings (Abernathy, 2016; Hiltz & Livesey, 2018).

Table 5. Breakdown of newspaper closings by ownership, January 1, 2008 to December 1, 2018.

| Owner | # of titles |

|---|---|

| Postmedia | 31 |

| Transcontinental | 30 |

| Black Press | 27 |

| Sun Media | 25 |

| Independent | 19 |

| Glacier Media | 16 |

| Torstar | 15 |

| Metroland | 14 |

| Other | 54 |

Source: Lindgren & Corbett, 2018.

NOTE: An independently owned news outlet is defined as a news outlet that is privately owned by a proprietor with only one or, at most, just a few local media outlets.

Table 6. Breakdown of newspaper launches by ownership, January 1, 2008 to December 1, 2018.

| Owner | # of titles |

|---|---|

| Independent | 15 |

| Metroland | 7 |

| Black Press | 4 |

| Your Community Voice | 4 |

| Transcontinental | 2 |

| Other | 8 |

Source: Lindgren & Corbett, 2018.

NOTE: An independently owned news outlet is defined as a news outlet that is privately owned by a proprietor with only one or, at most, just a few local media outlets.

Canadian researchers have linked chain ownership to compromised local content in newspapers. An analysis of content in Northumberland Today, a small daily that served the community of Port Hope, Ontario, found a significant decline in local coverage following the acquisition of the newspaper by the struggling Postmedia chain in 2014. Local content filled 89 per cent of the newspaper in 2008 (when it had a different name and proprietor). By 2017, the year the publication was shut down, more than three quarters of copy was syndicated wire service content (Miller, 2017). Another study pointed to a significant reduction in the amount and prominence of local news in the Toronto Star and Ottawa Citizen newspapers after 1970. Growing concerns about national unity likely accounted for some of the increased emphasis on national coverage, but chain ownership that emphasized cost-effective production and the sharing of national stories across the group was also cited as a explanation, particularly in the case of the Ottawa Citizen, where the decline in local reporting was the most notable (Buchanan, 2014).

Research in other jurisdictions, however, suggests chain-owned newspapers benefit in terms of competitiveness because certain costs can be reduced through the centralization of production and distribution (Ali, Schmidt, Radcliffe & Donald, 2018). There are also indications that chain-owned operations are more technologically competitive. One U.S. study noted that they are more likely to have adopted digital tools such as podcasting and video (Ali, Schmidt, Radcliffe & Donald, 2018). Similarly, a Reuters Institute examination of the transition from print to digital at newspapers in France, Germany, Finland and the United Kingdom concluded that where publications were part of newspaper groups, they benefited in terms of building an online presence from access to relevant expertise and digital tools (Jenkins & Nielsen, 2018).

Despite the newspaper losses to date, there is evidence that newspapers in Canada remain an essential part of local news ecosystems. Consistent with the Danish research that identified newspapers as anchors for local political coverage (Nielsen, 2015), for instance, a forthcoming study by Ryerson University’s Local News Research Project found that in the month prior to the 2015 federal election, newspapers generated more than half of all the local news media stories (54 per cent) about the races for members of Parliament in eight communities. Other types of local media contributed much less to the coverage, with television and online news sites each producing about 14 per cent of all stories and radio stations generating 18 per cent of news items (April Lindgren, personal communication, December 9, 2018).

Methodology

This survey was undertaken to create a snapshot of conditions at small-market Canadian newspapers and to generate data comparable to the results of a similar project undertaken in the United States (Ali, Radcliffe, Schmidt & Donald, 2018). The survey, therefore, included the same 23 questions asked in the American survey as well as 15 additional questions that solicited information on Canadian newsroom demographics, ethics awareness and training and audience engagement strategies. The survey questions and data are available in Appendix 1.

For consistency, this study, like its American counterpart, situates small-market newspapers in the space between online hyperlocal news outlets and publications that report on large metropolitan areas. Survey responses were solicited from newsroom and other employees working at daily or weekly publications with a print circulation below 50,000. In Canada, 30 of the country’s 90 daily papers have a total weekly print circulation below 50,000. Of the 1,029 community papers (defined by News Media Canada as papers that publish fewer than four times per week), 954 have a combined print and digital circulation below 50,000. Print-only circulation numbers for community papers are unavailable (Kelly Levson, News Media Canada, personal communication, December 16, 2018).

A total of 127 respondents completed the survey. All respondents answered 34 of the 38 questions. The other four questions required write-in responses and some respondents opted to skip them. Responses were anonymous. Consistent with the design of the American study, respondents were able to skip questions to “ensure the highest possible completion rate (also allowing participants to potentially bypass questions that were not relevant, or possibly unclear)” (Radcliffe, Ali & Donald, 2017, p. 20). The survey was in the field from February 5 to April 25, 2018. It was available online using the survey design website Survey Monkey and promoted on Twitter and other social media, through direct email to individual newsrooms/journalists and via industry newsletters and direct appeals circulated by the National NewsMedia Council and provincial community newspaper associations.

This report presents all results as percentages and includes the number of respondents to each question at the top of every chart and table.

Limitations

The conclusions and observations presented in this report should be treated only as indicative of what is happening to small-market newspapers because respondents were self-selecting and the sample, therefore, is not representative (Bethlehem, 2009). Readers should also be aware of the following limitations.

- 93 per cent of respondents came from Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan. There were no responses to the English-only survey from Quebec-based journalists.

- More editors (40 per cent) than reporters (20 per cent) responded to the survey and 28 per cent of respondents self-identified as owners of their publications.

- We had 127 survey responses but this does not mean we heard from 127 different newsrooms. More than one person from a single newsroom may have participated.

- Only two of the 127 respondents said they worked at a daily newspaper.

Survey respondents and the newspapers where they work

Key findings:

- Three quarters of respondents worked for publications that have a circulation below 20,000, most of them community papers that appear once or twice per week

- About two-thirds of respondents are editors/reporters

- About two-thirds of respondents have worked in local media for more than 10 years

- A majority of respondents worked in newsrooms with one to five staff editorial staff

- Nearly half of respondents were older than 50 years of age

- Almost all respondents worked at newspapers that were dependent upon advertising as a revenue source

Working in local media

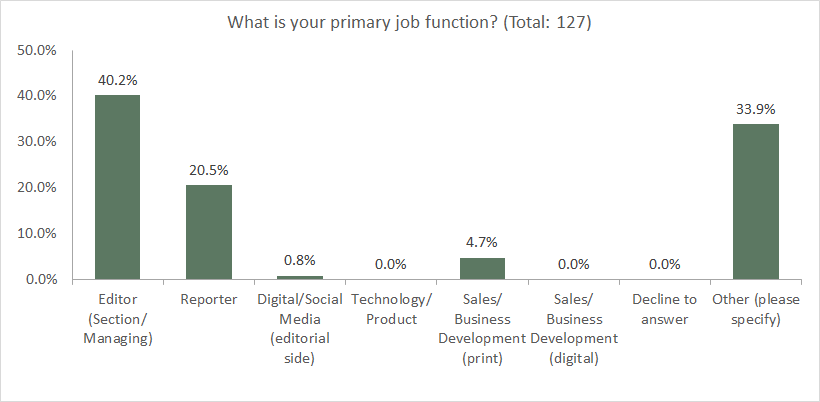

The majority of respondents (98 per cent) worked for community papers that produce print editions fewer than five times per week; 65 per cent worked for weeklies. When asked about their primary job function (Figure 1), the majority of respondents self-identified as either editors (40 per cent) or reporters (20 per cent). When we broke down the “other” responses, we found that 13 per cent of respondents identified their primary job function as that of publisher while 12 per cent said they performed all job functions.

Figure 1. Primary job functions of survey respondents

In response to a separate question asking if the survey participant was the owner of the newspaper, 35 respondents (28 per cent) self-identified as proprietors.

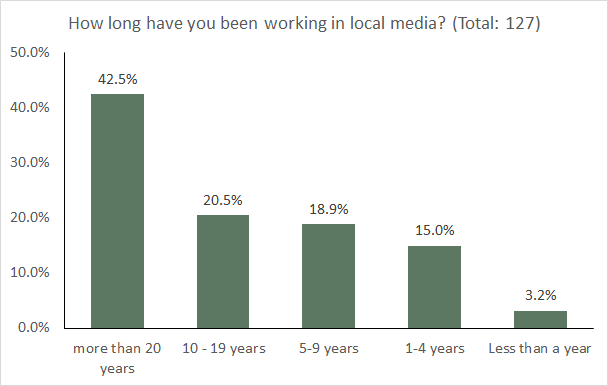

The majority of respondents who participated in the survey (63 per cent) had worked in local media for more than 10 years while only 18 per cent had fewer than five years of experience (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Experience working in local media

Demographics

All age groups were represented among respondents: 44 per cent were over 50 years of age, 39 per cent were between 31 and 49, and 17 per cent were between 18 and 30 years old. Only 3 per cent self-identified as a member of a visible minority group and only 4 per cent worked for ethnic media publications.

Almost all respondents (93 per cent) worked in newsrooms located in just four provinces: Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan. None worked at publications located in New Brunswick, Nunavut or Quebec (where the survey was only available in English). There was only limited representation from other Atlantic provinces and territories.

Newsroom characteristics

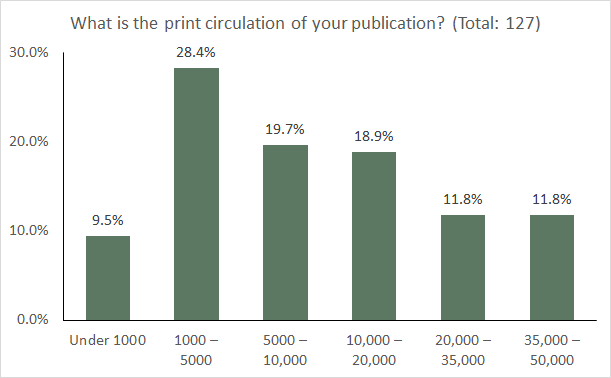

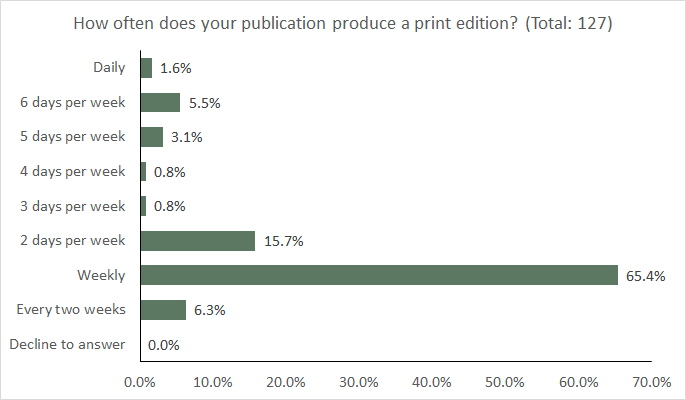

Every circulation size category was represented among respondents, with the largest group (28 per cent) associated with publications that have a print circulation between 1,000 and 5,000 copies (Figure 3). The majority of respondents (65 per cent) worked for weekly publications (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Circulation size of publications

Figure 4. Publication frequency

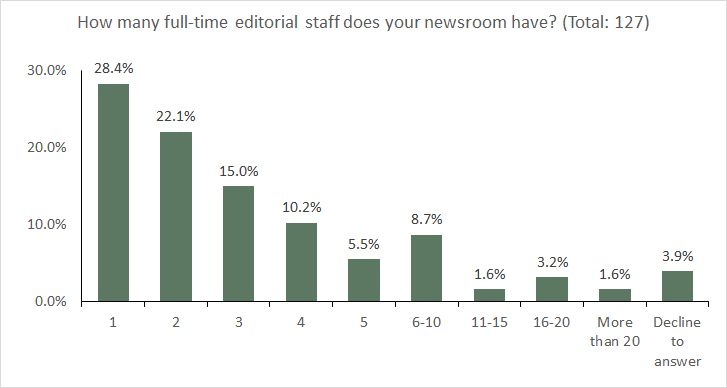

Fifty per cent of respondents work in a newsroom with only one or two full-time editorial staff (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Number of full-time editorial staff

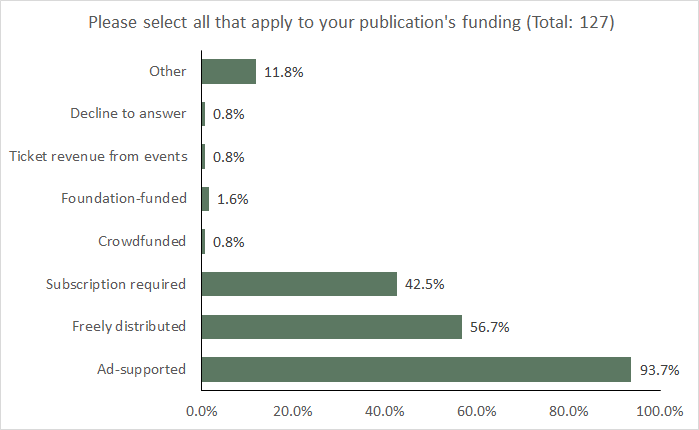

Almost all participants in the survey (94 per cent) said their publications generate revenue through advertising. While 42 per cent said the newspapers where they work raise revenue through print subscriptions, more than half (57 per cent) said the papers are distributed free of charge, which means they are completely reliant upon advertising revenue to survive (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Funding sources

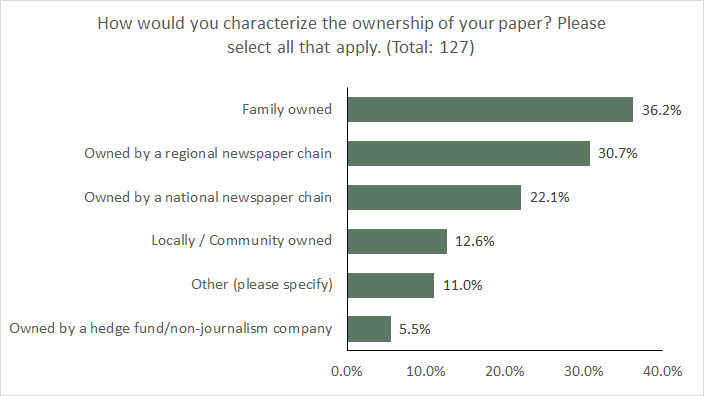

While their newsrooms were small, the majority of respondents (58 per cent) worked for a publication owned by a larger regional or national newspaper chain or a hedge fund/non-journalism company (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Publication ownership

Working life at a small-market newspaper

Key findings:

- The majority of respondents said they are spending more time on digital-related output than they did two years ago

- About a third said they are producing more stories and working longer hours compared to two years ago

- More than half said their newsrooms are smaller than they were in 2016

- 40 per cent of respondents said they worked 50 or more hours per week

Respondents painted a picture of an industry that has become increasingly demanding of its workforce. “We are..married business partners that haven’t taken a week off publishing the paper in 10 years. I’m tired and a little burned out,” we were told by one survey participant. “There is no ‘locum’ or temp agency that can do what we do.”

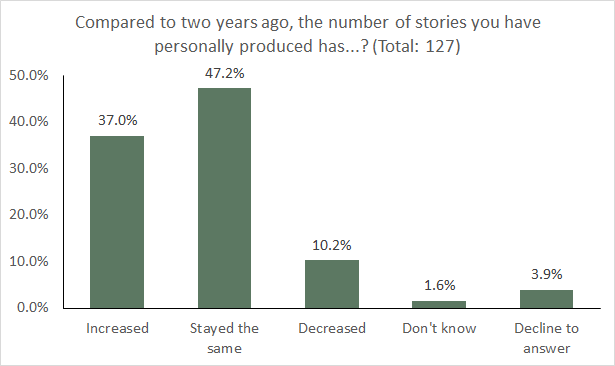

While 47 per cent of respondents said the number of stories they produce is the same compared to two years ago, 37 per cent said their output has increased (Figure 8). “Community journalists are overworked and underpaid,” one survey participant told us. “They are expected to do everything. I personally write copy for a 32-page paper on a weekly basis, usually writing 15-20 stories a week. Because of the time constraints, community journalists have very little time to do more in-depth reporting that could be more important and relevant to residents.”

Figure 8. Changes in story output compared to two years ago

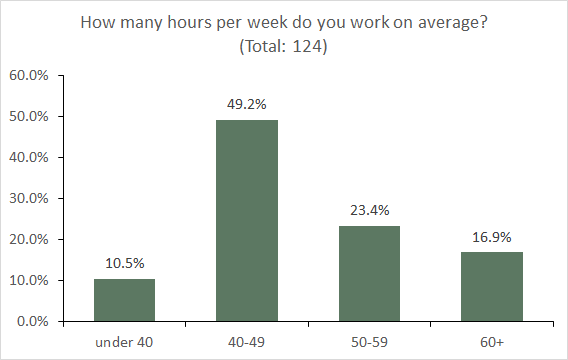

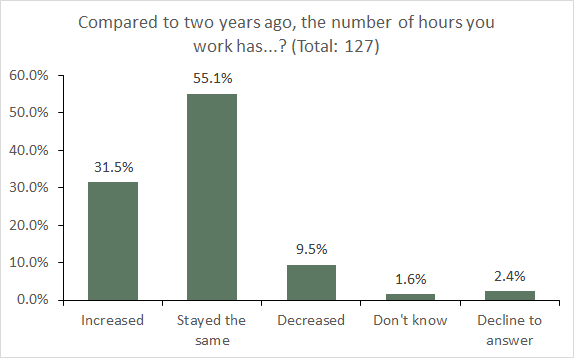

Forty per cent of respondents said that on average they are on the job more than 50 hours per week; another 49 per cent said they work 40 to 49 hours per week (Figure 9). About one third said they are working longer hours compared to two years ago (Figure 10). The added work associated with feeding the digital beast is part of the problem, we were told. Companies “make decisions that affect newsroom workloads without recognizing that they do so,” one respondent said. “A new website needs ‘fresh content,’ for example, but for a weekly newspaper reporter that is more work and responsibility. Managing Facebook and other social media engagement is also a responsibility that does not get considered by those making decisions.”

Figure 9. Average working hours

Figure 10. Changes in working hours compared to two years ago

Cuts to newsroom personnel—57 per cent of respondents reported that there were fewer editorial employees at their newspapers compared to two years ago—have also meant more work for the survivors. Complaints about workload and smaller newsrooms were in many cases linked to palpable concerns about the quality of the newspapers being produced. “It’s harder and harder to put out a quality product when staff cuts keep coming,” one respondent said. Another told us there is a “new generation of reporters who are overworked, underpaid, often so rushed they make mistakes.” Meanwhile, one survey participant told us, companies “claim they’re interested in content but make business decisions based solely on money and numbers.”

One respondent described what the inability to retain experienced reporters means to a small newsroom: “Many community newsrooms no longer have the veterans who have seen it all and done it all in the community. What happens when a mayor starts talking about an event from five years ago and not even your editor knows what the event was? You have to research and fact check what this was, but when a staff doesn’t even have people from five years ago it’s a problem.”

Digital Transformation

Key findings:

- Facebook was the most popular social media network among respondents for work and also for personal use

- While nearly half of survey participants said they produce video reports, the other half said they did not use any of the specific emerging tech tools (augmented reality, virtual reality (AR/VR), and chat apps) that we asked about in the survey

- Uptake for most digital tools was substantially higher among respondents who worked at chain-owned newspapers and at larger circulation newspapers

- Respondents wanted to know more about video reporting, live video, and podcasts, but were less interested in other emerging formats

- The majority of respondents learned about new technology/tools through online articles and by training themselves

One of the few studies done on digital adaptation at smaller Canadian newspapers raised concerns about the slow pace of change at community (weekly) newspapers in small-town and rural Canada. Even as older, less tech-savvy readers are being outnumbered by people who are more comfortable accessing online content, the study found that publications were slow to reorient from print-first to web-first news production (Nagel, 2015). That survey was conducted in 2011. Seven years later, our survey results show, much has changed.

A majority of respondents reported using some form of metrics to measure audience engagement (see the Building Audience and Engaging Community section for a more detailed discussion), which suggests an openness to using digital tools for purposes beyond disseminating news stories. It also points to a growing sophistication about the use of digital tools that goes beyond likes, shares and follows.

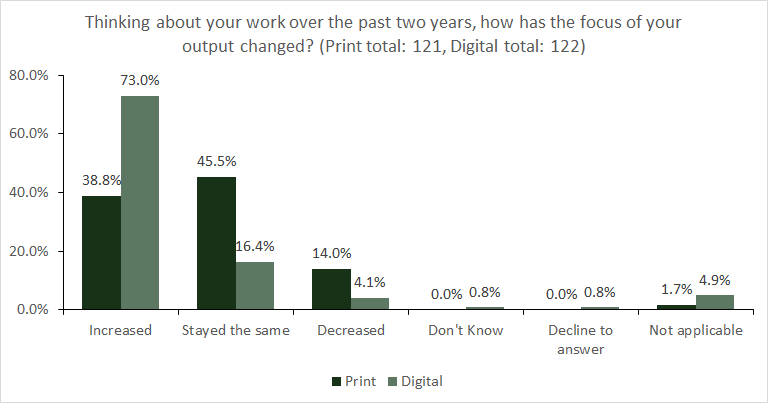

The survey results also point to a willingness to embrace digital tools: About three quarters of survey respondents said they now spend more time on digital-related output than they did two years ago (Figure 11). More than half of respondents (54 per cent) said they split their working time between their print and digital product.

“It’s not just about releasing a paper one or two times a week,” one survey participant said when asked about opportunities for small-market newspapers. “Papers can have a website where they post breaking stories, with a promise for more information in the next edition. They can use their talents to post videos, photo albums and podcasts.”

Figure 11. Changes in print and digital output compared to two years ago

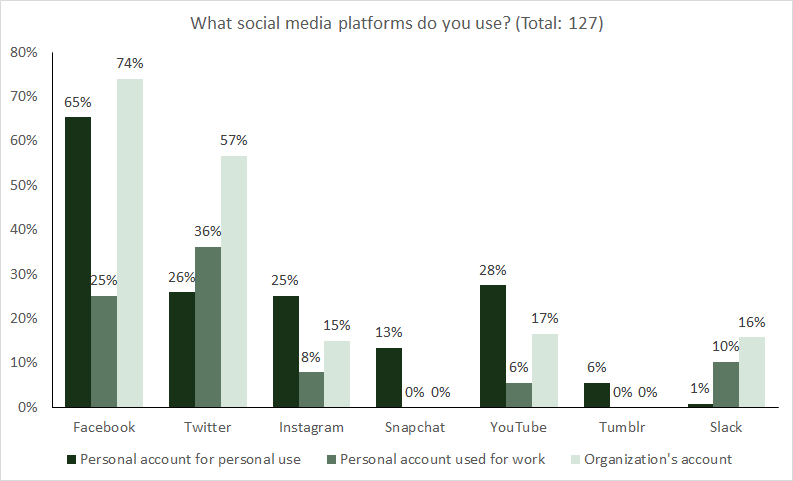

Most survey respondents in our sample also embraced some aspect of digital by incorporating major social media platforms into their work. “Social media reach,” as one respondent put it, “provides great advertising for a newspaper company as being the best source of reliable news for a community.”

Facebook remains the most popular platform for personal and professional use with 74 per cent of respondents reporting that they actively post to their organizations’ Facebook account. Twitter is the second most popular for personal and professional reasons, with 57 per cent of respondents actively using their organization’s Twitter account. Nearly 17 per cent of respondents said they used their organization’s YouTube account, and 15 per cent reported using their organization’s Instagram and Slack accounts (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Use of social media platforms

Emerging technology and reporting

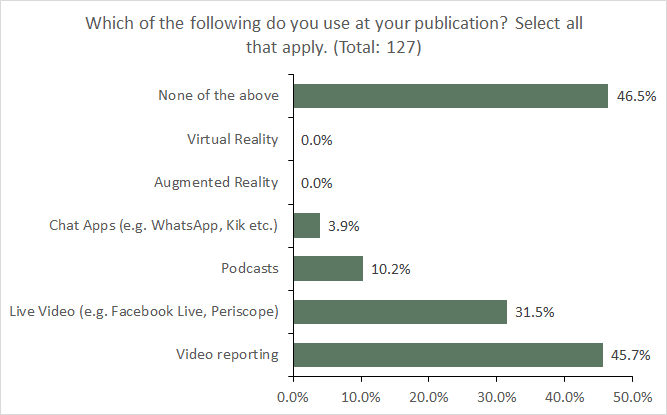

On the reporting front, 46 per cent of respondents reported using video in their newsroom, and 31 per cent reported using live video such as Facebook Live (Figure 13). The fact that video has been embraced over other technology is reflective of Canadian audiences’ evolving news consumption habits: 58 per cent of Canadians said they accessed a news video within the previous week, according to an online questionnaire conducted in February of 2018 by the internationally-based data company YouGov (Newman et al., 2018).

The reality, however, is that nearly half (47 per cent) of respondents said that they did not use any of the emerging technology we listed (Figure 13). We heard from survey participants who suggested there may still be lingering resistance to the new digital reality: “There are those who embrace (change) and adapt and those that refuse,” one respondent wrote. “And that has a significant effect on morale in a newsroom when you have those who are keen to engage being crushed by the sticks-in-the-mud that hate social media/digital.”

The resistance to video may also be strategic: most videos are consumed outside of the news publisher’s platform, and are instead typically viewed on social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube (Newman et al., 2018). Moreover, streaming video content requires fast internet connections, and slower connections in more rural areas may temper audience and publisher interest in video formats (Radcliffe, Ali & Donald. 2017).

There was limited use of podcasts (10 per cent) and chat apps (4 per cent), and no reported use of augmented or virtual reality (Figure 13). One respondent explained the reluctance to embrace these more advanced digital tools like this: “We don’t need the fanciest or newest technologies to tell a good story. Community newspaper reporters are driven and can do a lot with very little. We need to double down on what the community wants to read and see – engaging photos, interesting and informative stories, and occasional videos.”

Figure 13. Use of reporting technology

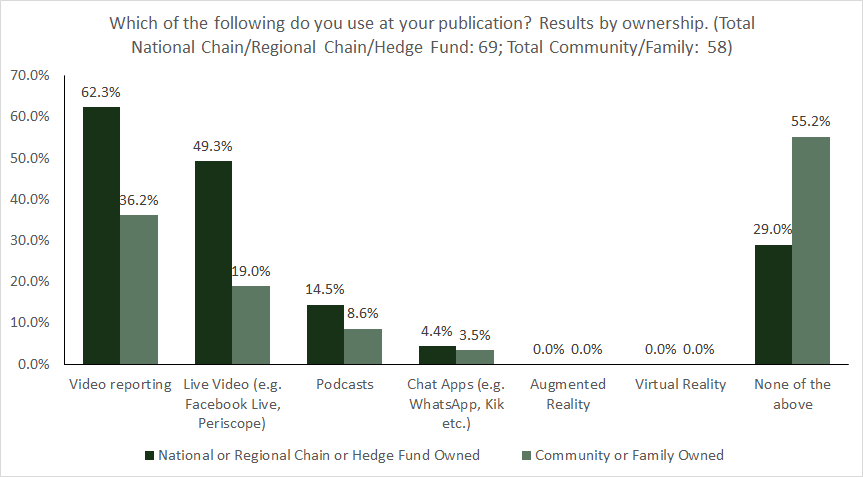

Ownership, meanwhile, is clearly associated with the willingness or ability of small-market newspapers in Canada to embrace almost all categories of digital tools: The uptake for most tools is substantially higher among respondents who said they worked at chain-owned newspapers (Figure 14). This is consistent with European findings (Jenkins & Nielsen, 2018) and the results of U.S. research that found that while family-owned newspapers exhibit a commitment to place and their local roots, “they tend to be the newspapers with the weakest digital uptake. In contrast, chain ownership brings digital resources, but loses local autonomy” (Ali, Schmidt, Radcliffe & Donald, 2018, p. 8).

Figure 14. Use of reporting technology by type of ownership

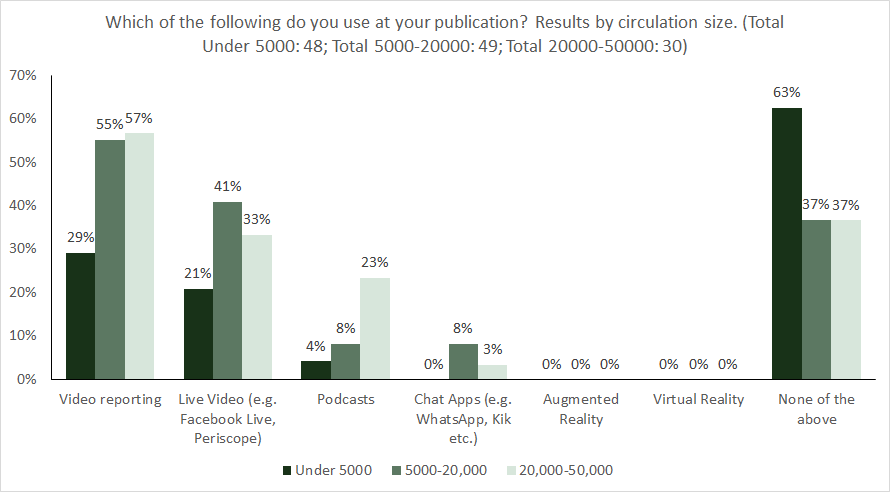

Larger circulation publications were also much more likely to use digital tools for reporting. Among newspapers with a print circulation below 5,000, 63 per cent used none of the tools on our list (Figure 15).

Figure 15. Use of reporting technology by circulation size

Nearly half of respondents expressed significant interest in learning about video (50 per cent) and live video (52 per cent). And while only a small minority of respondents said they used podcasting in their newsroom, more than one third (39 per cent) expressed interest in learning about the format (Table 7). This likely reflects the growing popularity of podcasts and the audio format’s ability to attract younger audiences (Newman, Fletcher, Kalogeropoulos, Levy & Nielsen, 2018). Having said that, slightly more respondents (43 per cent) indicated that they were not interested in learning about podcasting, which may speak to the high cost in terms of time and money associated with producing quality podcast products and the tough competition for listeners and advertisers that new podcasts face when entering the market (Beard, 2018).

Table 7. How interested are you in learning about these emerging technologies? (1 = not interested; 5 = very interested)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | # of Respondents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video reporting | 21.0% | 9.2% | 19.3% | 23.5% | 26.9% | 119 |

| Live reporting | 18.6% | 8.5% | 21.2% | 27.1% | 24.6% | 118 |

| Podcasts | 28.6% | 14.3% | 17.7% | 21.0% | 18.5% | 119 |

| Chat apps | 52.7% | 23.6% | 10.0% | 8.2% | 5.5% | 110 |

| Augmented reality | 56.8% | 13.5% | 12.6% | 11.7% | 5.4% | 111 |

| Virtual reality | 55.8% | 15.0% | 13.3% | 11.5% | 4.4% | 113 |

Source: Lindgren & Corbett, 2018.

Beyond podcasting and video formats, respondents were less interested in learning about other emerging technologies such as virtual reality and augmented reality (Table 7). This likely reflects how little these technologies are employed even in larger newsrooms.

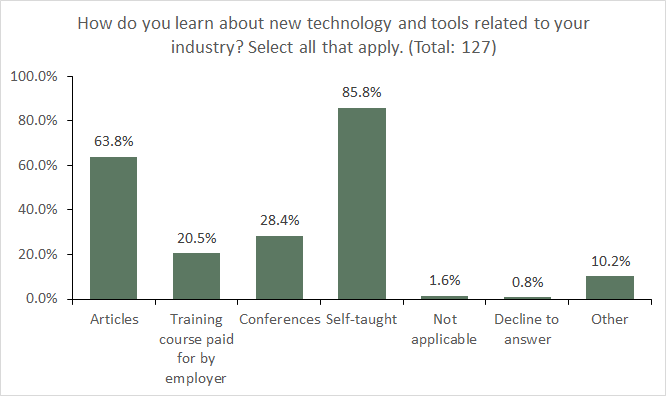

It is conceivable that the ways in which respondents learn about new technology may impact their levels of interest in learning about it. The vast majority of respondents (86 per cent) said they were “self-taught,” and 64 per cent said they learned about emerging technology through articles, such as those published on Nieman Lab, Poynter, Mediashift or J-Source. In contrast, more formal methods of learning were less prevalent. Less than one third said that they learned about emerging technology by attending conferences, and only 20 per cent indicated that they enrolled in a training course paid for by their employers (Figure 16).

Employers’ lack of investment in training and professional development was noted by respondents. “Lack of mentors/training for reporters,” “learning and keeping up with technology” and “lack of investment by companies into newsroom resources – either technologically, training or staffing” were cited when we asked about challenges facing small-market newspapers. One respondent noted that the hollowing out of newsrooms means it’s even difficult to learn through observation, noting that “as a new journalist starting out in a small market under a young editor, I have found it difficult to learn from existing reporters because there are very few to fall back on in my coverage area.”

Given the fact that most respondents learned about new technology related to their industry through their own initiatives, a larger discussion on learning opportunities in the newsroom is warranted to further explore the role that investment in training plays in digital uptake.

Figure 16. New technology training

Ethics awareness and training

Key findings:

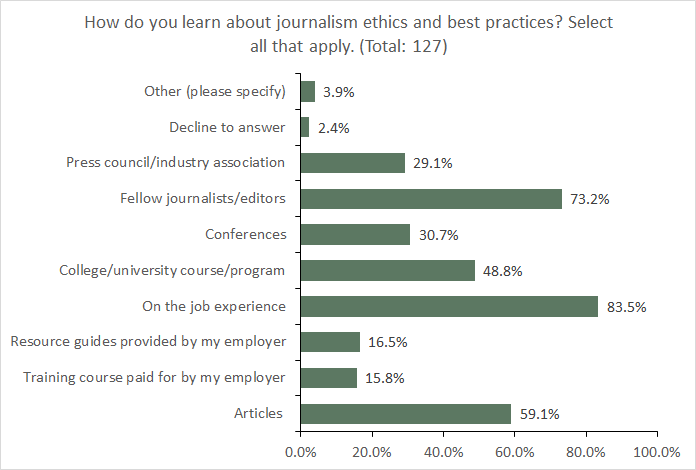

- Most respondents said they learn about journalism ethics and best practices on the job, from fellow journalists and published articles

- Only about 15 per cent of respondents said they obtained ethics training from resource guides and ethics training courses paid for by employers

- The majority said they considered journalism best practices and ethics when posting to both their personal and organization’s social media accounts

- Nearly half of respondents said they learned about ethics and best practices from post-secondary programs or courses

Journalism standards and ethics provide reporters and editors with guiding principles on what constitutes proper professional conduct. Although several scholars have expounded on the theoretical implications and limitations of the study of journalism ethics (Ward, 2010, 2013, 2015; McBride & Rosentiel, 2014), for the purposes of this study, ethics are considered chiefly as a professional, applied enterprise (Black, Steele & Barney, 1999).

Got a beef with your local paper? Take your complaint to the National NewsMedia Council

The National NewsMedia Council was established in 2015 with two main aims: to serve as a forum for complaints against its members and to promote ethical practices within the news media industry. The council deals with matters concerning fairness of coverage, relevance, balance and accuracy of news and opinion reporting.

At present, the NNC is composed of more than 600 member news organizations ranging from small community newspapers to large dailies and digital-only news organizations.

The council is comprised of 17 directors – nine selected as members representing the public and eight representing news organizations that are part of the NNC. The Council’s chair is always a public director.

In Canada, the framework of applied journalism ethics has been constructed, and continues to evolve, in conjunction with the work of several national organizations. In English Canada, specifically, this cascading system of practical standards is rooted in a confluence of documents including the Canadian Association of Journalists ethics guidelines; the Canadian Press Style Guide; the Canadian Association of Broadcasters’ Code of Ethics; and the Radio Television Digital News Association’s Code of Journalistic Ethics.

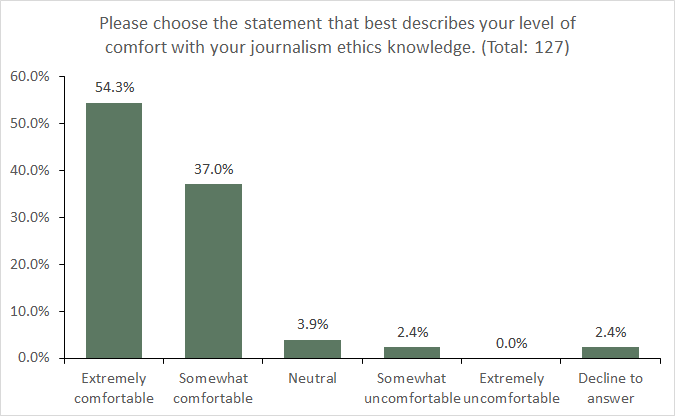

The survey results provide insight into what Foreman (2015) refers to as ‘ethics awareness.’ As Figure 17 shows, 54 per cent of survey respondents consider themselves to be ‘extremely comfortable’ with their knowledge of journalism ethics, while another 37 per cent consider themselves to be ‘somewhat comfortable’ with their level of ethical expertise.

Figure 17. Knowledge of journalism ethics

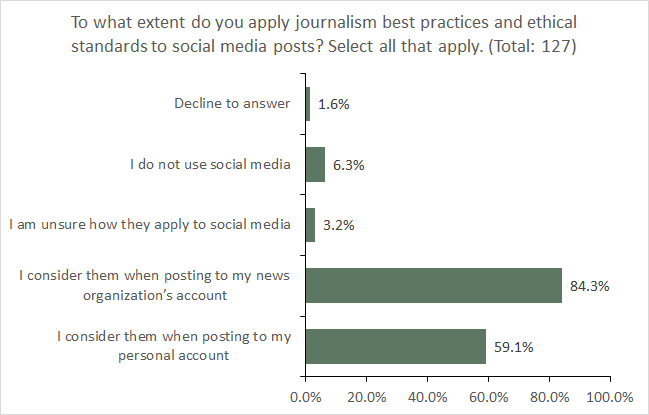

The majority of respondents also said they considered journalism best practices and ethics when posting to both their personal (59 per cent) and their organization’s (84 per cent) social media accounts (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Use of journalism best practices and ethics

On the surface, these results are encouraging. At a time when many news organizations and industry groups are launching trust-building efforts and transparency projects, they underscore that journalists and news organizations are striving for a method of reporting that is transparent, independent and committed to the production of verified, timely, and relevant information. The adherence to shared standards of practice, moreover, helps to nurture the idea of a professional identity among journalists.

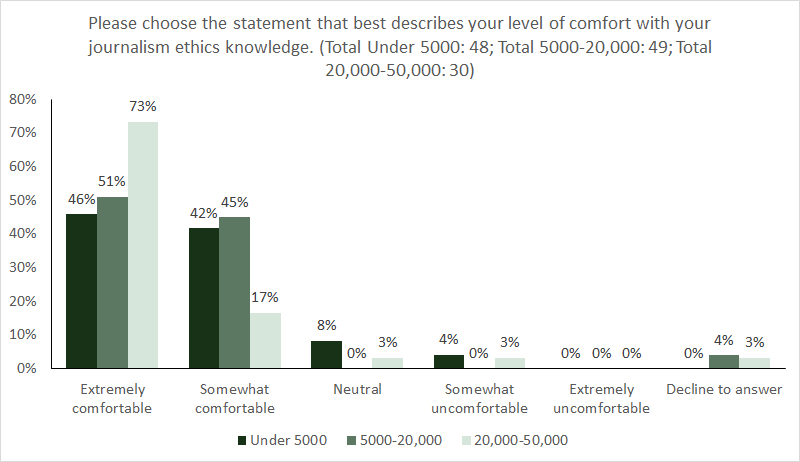

A closer look at the data, however, highlights some shortcomings. Respondents at larger newspapers, for instance, tend to be more at ease with media ethics: 73 per cent of respondents at publications with circulation in the 20,000 to 50,000 range said they were “extremely comfortable” with their ethics knowledge. By comparison, only 46 per cent of respondents at the smallest circulation newspapers (below 5,000) categorized themselves as extremely comfortable with their knowledge level (Figure 19).

Figure 19. Knowledge of journalism ethics by circulation size

The survey data also suggest employers themselves aren’t investing substantially in ethics training or the development of in-house ethics guides: Just 17 per cent of respondents said they learned from guides provided by their employer and only 16 per cent said they learned from a course paid for by their newspapers (Figure 20). Thirty-one per cent said they learned about journalism ethics and best practices by attending conferences.

Indeed, the data suggest that when it comes to keeping abreast of emerging ethics-related issues, respondents were largely on their own. As Figure 20 shows, 84 per cent of survey respondents said they learn about journalism ethics and best practices from ‘on the job’ experience. Seventy-three per cent also reported learning about ethics, standards and best practices from fellow journalists while 59 per cent reported learning from articles published by J-Source, MediaShift, and the Nieman Lab, amongst others.

Figure 20. Journalism ethics training

Given that smaller publications may be vulnerable to pressure from large advertisers seeking to influence news coverage, and given the evolution of best practices with respect to reporting effectively on issues such as mental health, suicide, and Indigenous communities, further research exploring the relationship between access to professional development and how it shapes news agendas and reporting would be worthwhile.

The paucity of employer-supported ethics training also highlights the importance of the foundational ethics education offered at post-secondary institutions in Canada: Nearly half of survey respondents (49 per cent) reported they learned about journalism ethics and best practices from courses or programs offered at college or university. Given that nearly half of our respondents relied at least in part upon their post-secondary ethics training to navigate an increasingly complex world, research documenting what is being taught at journalism schools and best practices for teaching in this subject area would be of value. Do courses simply review different codes of practice or do they employ case studies that explore competing interests? Moreover, how are journalism ethical issues framed and presented in courses with respect to the evolving frontiers in data journalism, the use of artificial intelligence, algorithmic transparency, or the practice of de-indexing? Broadly speaking, being able to better understand what journalists consider an ‘ethical issue’ will help educators, industry groups, and other key stakeholders to address the need and demand for new educational resources in the future.

Building audience and engaging community

Key findings:

- More than three-quarters of respondents work in newsrooms that use some sort of metrics tools/software to measure audience engagement

- More than one third said their publications had launched an editorial campaign on an issue that is important to their community

- Almost all publications represented in the survey had published articles written by community members

- Nearly one third of respondents said their publications had hosted events related to an issue affecting the communities they serve

- While some respondents were skeptical about the term ‘engagement’ and dismissed it as little more than a buzzword, many others saw it as a way to foster conversations with readers and play an active role in local debates

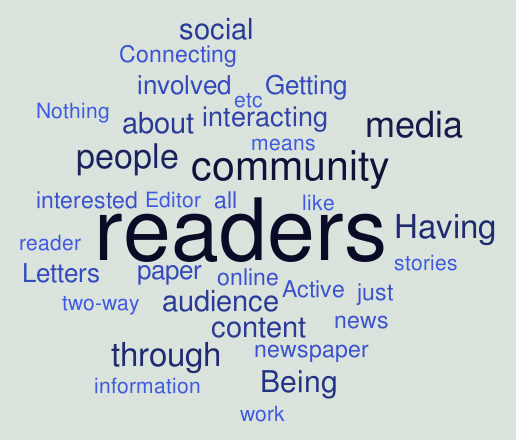

Figure 21. Words mentioned five or more times to describe engagement

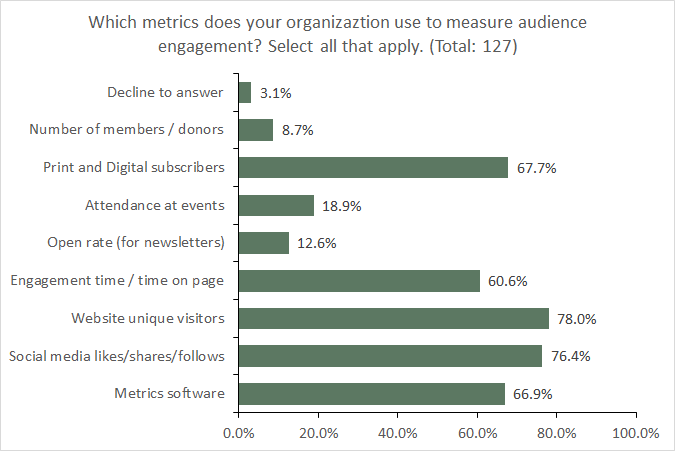

Developing relationships with readers – or audience engagement—is increasingly considered integral to building trust and diversifying revenue streams for local news outlets (Hansen & Goligoski, 2018). The majority of respondents (76 per cent) reported using social media metrics such as likes, shares, and follows to measure audience engagement with their stories. Respondents also reported using a number of other forms of metrics, which Neheli (2018) defines as “units of measurement that reflect a specific element of audience behavior.” For instance, 78 per cent used the number of unique website visitors, 68 per cent used the number of digital or print subscribers, and 67 per cent used some form of software, such as Chartbeat, to measure audience engagement (Figure 22).

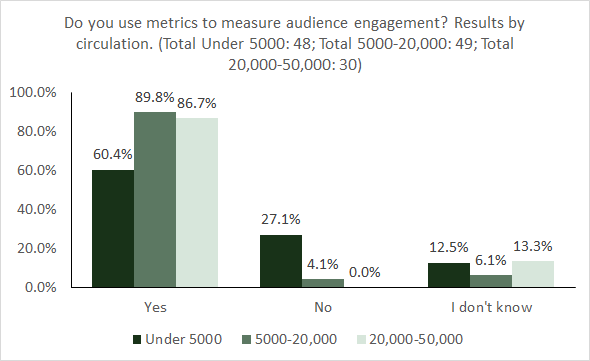

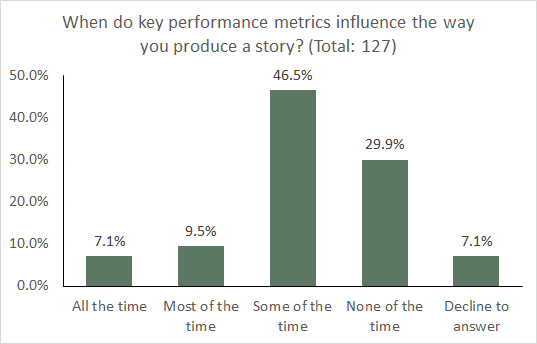

The use of metrics, however, was much more common among larger (around 90 per cent) rather than smaller (60 per cent) publications (Figure 23). While the majority of respondents (63 per cent) said metrics influenced how they produced a story at least some of the time, nearly one third said they did not consider metrics at all when producing stories (Figure 24). This may have something to do with the availability – or lack thereof – of such metrics in smaller newsrooms. It might also reflect what scholars have identified as tensions in newsrooms about the use of metrics to shape what stories get told. There are, for instance, journalists who recognize how metrics can be useful in determining what stories to tell. Others, however, are concerned about relying upon what has been read in the past to shape stories produced in the future (Ali, Schmidt, Radcliffe & Donald, 2018; Neheli, 2018). One survey respondent, for instance, told us that “due to page view bench-marking, finding the time to write important stories that will not perform well online such as mental health, local council, board meetings” is a challenge.

Figure 22. Use of metrics tools to measure audience engagement

Figure 23. Use of metrics by circulation size

Figure 24. Influence of metrics on story production

To explore engagement strategies in more depth, we asked respondents what the term engagement meant to them (Figure 21). Some respondents had little use for the term – in one case it was dismissed as a “stupid buzzword for talking and listening to the public, or getting them to follow us on social media.” Others offered specific definitions such as “page views, also likes and shares,” “letters to the editor,” “they come to us for information, answers, promotion and advertising,” “clicks” and “people reading stories, whether in print or online.”

A second group of respondents discussed engagement in terms of fostering real conversations with readers. It “is more than metrics from social media—it represents a bona fide relationship with readers whereby we’re getting information and reactions from them as much as they’re receiving news from us,” one respondent said. Another described engagement as “an active two-way conversation with our audience/readers. Can be in person, online through the comments section, real-time social media conversation… anything that helps readers feel like they are part of the story and not just being given information or told what to think. Help them take ownership of local media and feel like we care what they have to say, rather just looking at them like ‘clicks’ to sell to advertisers.” One respondent sounded a cautionary note, defining engagement as “using social media to interact with readers” but also noted that his/her employer still has a way to go to achieve that goal: “I’d like to have more two-way interaction, but at my organization, social media is still being used to broadcast rather than have conversations with readers.”

Finally, a third group talked about engagement in terms of their newspapers’ role as an active participant in local debates. One respondent, for instance, defined engagement as “being involved in the community, not just reporting on what happens,” while another said it is about “being involved in the lives of our readers. Having readers involved in the paper.” Others saw their publication as engaging audiences by providing a public forum for the discussion of topics people considered important. Engagement is about “giving the community an outlet to express ideas and concerns. Demonstrating a unified voice for the town’s residents,” one person commented.

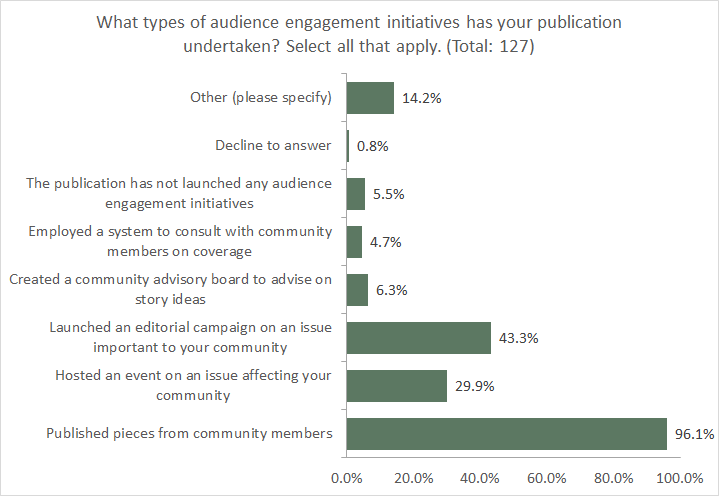

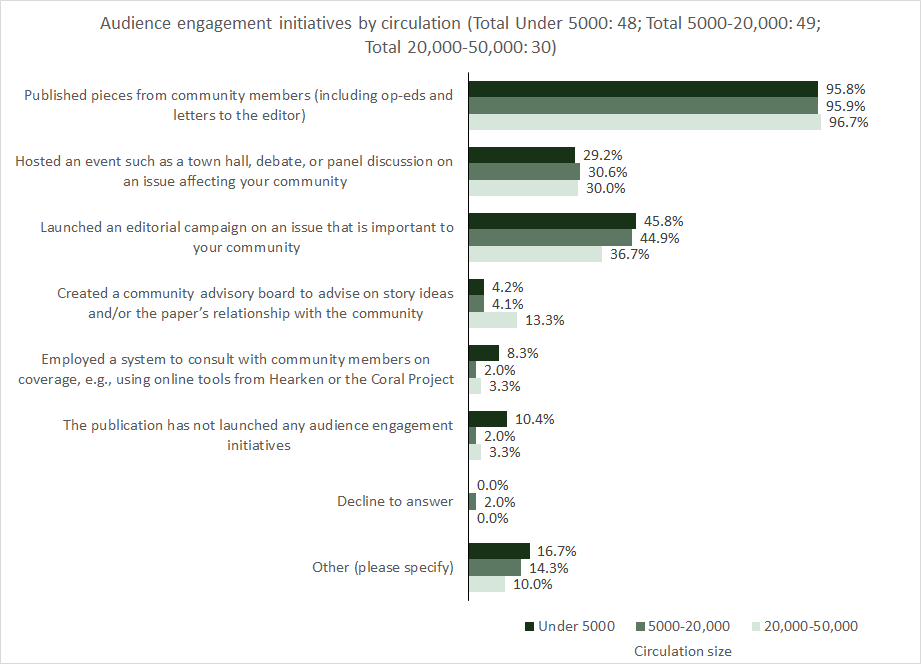

In terms of actual engagement strategies, almost all respondents said their publications print contributions from community members and 43 per cent said their newspapers had launched an editorial campaign on an issue important to people in their coverage area (Figure 25). Smaller publications seemed to be more active in this regard: 37 per cent of respondents from larger circulation newspapers (20,000 to 50,000 copies) said their publication had launched a campaign compared to about 45 per cent of papers with a circulation below 20,000 copies (Figure 26).

Figure 25. Types of engagement initiatives

Figure 26. Types of engagement initiatives by circulation size

Only about one third of respondents said their publications had organized an event in the community they cover despite a growing body of evidence that suggests events are a way to connect with readers, collect feedback and generate news content for the publication. Research from the U.S.-based Local News Lab, suggests events are also “a proven way to diversify a publisher’s revenue stream” (Stearns, 2017, p. 1) because advertisers and event sponsors see them as a guaranteed way to connect with a known pool of potential customers.

The limited uptake on events is partly a resource issue: Most respondents (81 per cent) worked for small newspapers with one to five newsroom staff, which suggests nobody has time to take on jobs beyond getting the paper out on time. Newspapers in small communities of just a few thousand people might also find it a challenge to attract audiences to multiple events over time.

News reporting and relationship building: A two-way street

Newsrooms in Canada and elsewhere are adopting and experimenting with strategies that build relationships with their audiences. Examples include:

- free email newsletters: Newsletters have emerged as a potent form of communication that puts news outlets in touch with loyal audience members (Breiner, 2018).

- initiatives designed to attract younger readers: One chain-owned Danish newspaper in a community of 15,000 set out to attract younger readers by working with a local teacher to develop curriculum for a seven-week journalism course in a local high school. More than 100 people subsequently attended a final event, sponsored by a local bank, to discuss proposed solutions to issues the students covered during their course (Lichterman, 2018).

- story circles that build trust, identify community concerns, propose solutions and shape the news agenda: In 2018, The Discourse, a Vancouver-based digital news outlet, held its first story-circle in the Toronto suburb of Scarborough in the city’s easy end. Sixteen people showed up for a conversation with Discourse journalists about how the news organization could tap into a broader range of sources and better cover Scarborough stories in a way that challenges stereotypes and more accurately reflects what is happening in the community (Bhandari, 2018).

While events were not top of mind, some respondents volunteered specific information on other engagement activities. Here’s what some of them told us they were doing to build relationships with their audiences.

Engagement initiatives at newspapers with print circulation below 5,000

- Sponsorship of community events, donation of prizes, staff members volunteering at events, and with community organizations.

- We have been interviewing local people who have had interesting lives or have done interesting things.

- Marketing opportunities ie: sidewalk sale.

- Developed a Web platform to facilitate flow of information between community organizations.

- Readers’ survey conducted in 2017.

- On our most controversial issues, we have at times sought guest columns from those on both sides of the issue. We have also asked for comments via Facebook.

- I have elementary (school) students in a newspaper club writing articles for our paper as well as regular columns by knowledgeable community members and some who write for fun.

- We’ve done some work with local schools helping students get their stories published in our weekly paper.

Engagement initiatives at newspapers with print circulation between 5,000 and 20,000

- Solicit questions through social media to ask of interviewees; ask for story tips and feedback on coverage; have staff attend community functions and speak with people there.

- A few yearly print format contests.

- Hosts community events (i.e. Easter Egg Hunt) and supports community events (i.e. Summer Festival).

- Constant social media engagement.

- Created various features, including our Community Leaders Awards, where we ask readers to nominate individuals, based on their leadership in the community, within different categories.

- By creating a newspaper with local news, week in and week out.

- Inviting people to comment on articles.

Engagement initiatives at newspapers with print circulation between 20,000 and 50,000

- We do community projects every month, whether it’s helping to hand out hotdogs at the firehall during the Halloween bonfire or talking to a high school writing class.

- Worked with other local media on an advisory council (which includes members of the public) on issues of discrimination and representation in the local media.

- Having reporters and editors go to community events to actively ask opinions on matters of public interest.

The outlook

Key findings:

- Nearly half of respondents said they feel very secure or slightly secure in their positions, while slightly more than one third said they feel slightly or very insecure

- Respondents were divided about the future of small-market newspapers—younger people were much less optimistic than older survey participants

- Respondents who self-identified as owners were overall more positive than negative about the outlook

- Respondents were concerned with increasing competition for advertisers and audiences from digital platforms and non-local news sources

- The perception that print is no longer relevant was identified as a significant hurdle that adds to the challenge of attracting readers, advertisers, and young journalists

- Attracting and retaining qualified, trained staff is a major challenge

- Maintaining a local focus and producing unique, local content were cited as the biggest opportunities/advantages for small-market newspapers

- Respondents said they are a trusted source of information in their communities and that this gives them a competitive advantage

Concerns about disruption in the newspaper sector were reflected in the survey results. About one third of respondents (35 per cent) said they feel slightly or very insecure in their positions while 46 per cent of respondents said they feel very secure or slightly secure (Figure 27).

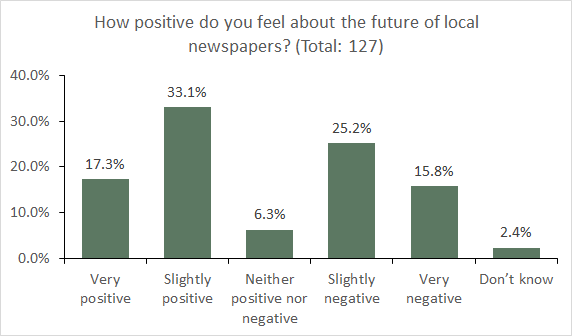

Figure 27. Job security

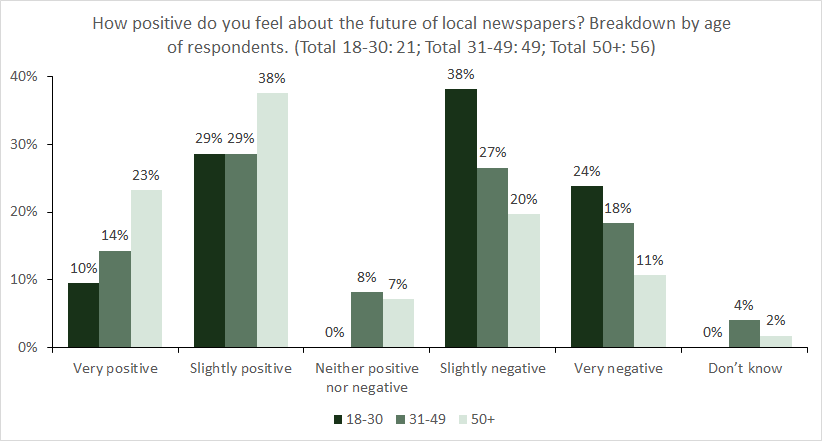

Respondents were also divided about the future of local newspapers: 50 per cent were “very positive” or “slightly positive” while 41 per cent said they were “slightly negative” or “very negative” (Figure 28).

Figure 28. The future of local newspapers

Figure 29. The future of local newspapers by age

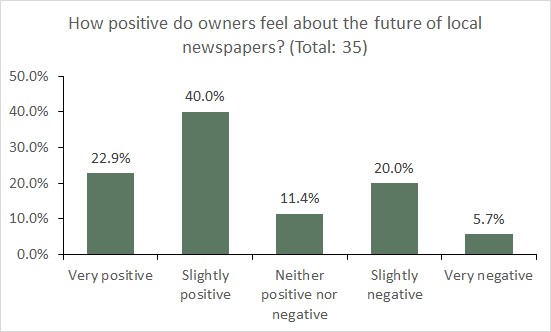

Among respondents 50 years and older, 60 per cent were slightly or very positive, while a clear majority of younger respondents (18-30) were slightly or very negative about the future (61 per cent) (Figure 29). Respondents who identified as owners tended to more positive than negative about the future (Figure 30).

Figure 30. Owners’ feelings about the future of local newspapers

Challenges

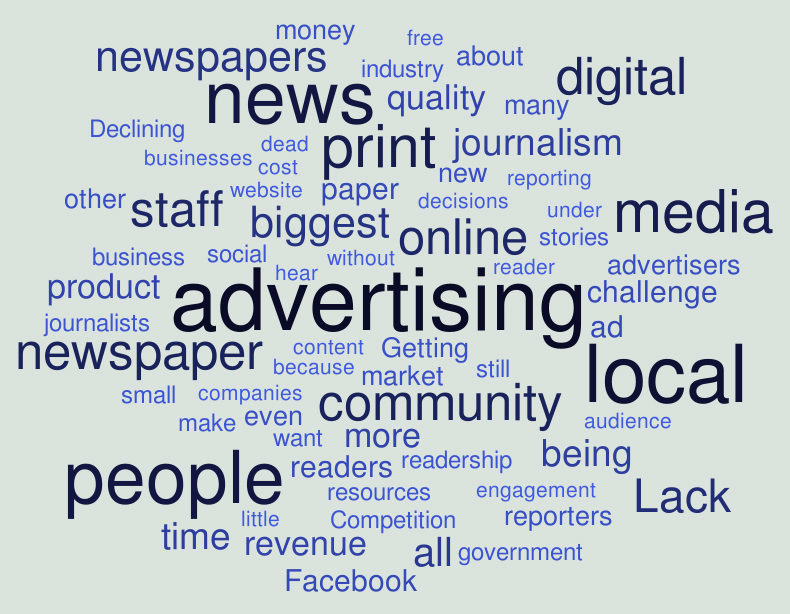

We asked survey participants to cite the challenges they face beyond time and money issues but many of their responses nonetheless were linked in some way to constraints in these two areas (Figure 31). A number of respondents, for instance, identified diminishing government advertising as an issue given that so much of it has been moved online. Others pointed to corrosive competition as problematic: “Cheapskating of resources by (a) competitor has undermined print in our region,” observed one respondent who was concerned that cost-saving initiatives by a competitor had paved the way for similar cuts at other publications.

Figure 31. Words mentioned five or more times to describe challenges

The most widely cited concern we heard had to do with securing advertising revenue. Specific issues included “convincing advertisers we’re still relevant and helping them understand people who get our paper want it AND read it,” “advertisers splitting their marketing budget between so many mediums,” and the “misrepresentation of digital ad benefits.”

Respondents identified competing with Facebook and Google for ad revenue as a major difficulty. The two digital giants, one respondent said, “have swallowed the web and are not subject to the same taxes, cost structure and legal obligations of real news generators.”

Others pointed to the pressure that an increasingly digital world is putting on print publications. One respondent explained a recurring dilemma: “The decision (is) whether to be ‘first’ with the news, given this digital age and the speed of social media and online publishing, or to hold back and do a better job of reporting the story before posting or printing the article.”

Still others cited difficulties convincing audiences that local news matters especially when competing with nonlocal news sources. One respondent said, “The digital push in small communities is difficult because they’re getting all of their information nationally and internationally somewhere else.” Being “as fast, as foolproof, as newsrooms that are 10 times our size,” was also cited as a challenge.

A small group of respondents linked digital competition and online competitors that “go for clicks above all else” to eroding public trust and journalism standards. This is bad for local newspapers, one respondent explained, “not only because they siphon off what little ad money is left after Google and Facebook, but because they force us (to) emulate them…in order to retain our audience online and thus our advertisers. It’s a slippery slope.”

In addition to competing with digital platforms and larger publications, some respondents cited their publication’s difficulties with monetizing their own digital products. “Digital revenue is nickels and dimes—at the local level there isn’t enough CPMs [cost per thousand, a marketing metric] to generate enough revenue to afford providing a quality product,” one respondent said. Another observed that “getting people to pay for the news, instead of getting it for free online” was a major challenge, a sentiment echoed by other respondents.

One of the most common challenges cited was the need to defend the relevance and viability of small-market newspapers to both advertisers and audiences. The perception that their print product is in its death throes was identified as a major hurdle in and of itself. As one respondent put it: “The biggest challenge is showing people that we have a future. People hear messages about how the newspaper industry is in big trouble, and it filters down. Advertisers hear this message and they’re less willing to advertise. Students coming out of journalism schools hear about papers that are closing. They don’t hear about the opportunities that exist with weekly and small-city newspapers. And people don’t see how many community newspapers are diversifying, through their websites and through podcasts.”

Other oft-repeated challenges that make it difficult to put out a quality product related to understaffing and a shortage of sufficiently trained personnel. Respondents pointed to layoffs and the difficulty of attracting qualified applicants as a problem. While the survey sample is not representative, the age distribution of our respondents—44 per cent were older than 50—does raise a red flag about potential problems down the road. If indeed the majority of editors, journalists and proprietors are older, what happens when they all start to retire in a decade or so? This question is particularly relevant if younger people, discouraged by low pay and few opportunities for advancement, aren’t waiting in the wings to take over.

In addition to recruitment challenges, respondents also identified a lack of training for existing staff and potential candidates, pointing specifically to issues such as “long-time reporters lacking digital skills” and the “quality of graduates from journalism programs.”

Some respondents, most of them employees of major newspaper chains, cited poor decision-making ‘from above’ and “inept moves” by the chains as a drag on growth. Staff cuts, lack of newsroom investment and the additional work associated with social media and other digital tools were offered as concrete illustrations. “We’re the ones on the ground,” one respondent said. “We know what our readers want, but owners continue to chase pie-in-the-sky ideas looking for quick wins they can turn into immediate profits. Local media is changing. We should be playing the long game. Management, companies and owners just aren’t listening.”

Taking the pulse of small-market newspapers across Canada

Freelance journalist Angela Long recently completed a cross-Canada tour visiting more than 20 towns, most of them small communities with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants. Her mission, chronicled in a series of stories published by J-Source.ca, was to meet the people covering local news in rural and small-town Canada. What follows is an edited interview.

What did you do in each community you visited? I tried to spend at least a few days in each place to get to know it. I interviewed publishers, reporters, locals – whoever would talk to me. All the papers I visited were weekly, or bi-monthly. Initially my plan was to focus on independently-owned papers (or “indies” as some call them), but in some parts of the country this option just didn’t exist. While on the road, my rule was to stop in every small town and, if there was one, buy the local paper. I collected dozens.

What did you learn about the financial situation of small newspapers? Everyone, almost without exception, had less revenue than in the past, but publishers said they were still making a profit. One reason for less profit, the biggest reason for most publishers, was the loss of government advertising. But many said the small town paper was still a good way to make a living. Less revenue often resulted in fewer newsroom staff and fewer stories, however, and publishers are therefore trying to branch out into other business ventures, such as stationery sales, printing services, specialty publications. Usually family members were keeping the boat afloat by reporting, editing and generally getting the newspaper out on deadline each week.

Are smaller papers embracing digital news? Digital was often a challenge because many areas I visited lacked connectivity, or had very slow and/or expensive internet service. Sometimes when I was driving, there would be no cell coverage for thousands of kilometres. Most publishers were interested in improving their digital presence but said their readers and advertisers still preferred print. Many said the money was still in print. Some expressed a need/desire for more training and improved infrastructure so they could branch out into digital, but they still worried about how to monetize digital. That said, most had some sort of digital presence–Twitter, Facebook, a website. Many offered digital subscriptions.

What role are these newspapers playing in their communities? The papers seem well loved, or at least supported, by their communities and are read by young and old alike. From what I discovered, newspapers—or any form of local news media—play a critical role in rural Canada. They act as information providers, storytellers, and watchdogs in remote places where few other options exist. They are the experts of their community, their geography. They play an important role in community building and democracy. Some of the papers also play a role in reconciliation, either by reporting on First Nation communities in a manner adhering to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission calls to action, or by providing a forum for First Nation communities to tell their own stories.

How did the journalists/newspaper proprietors you met view the future? In general, everyone involved in rural journalism was passionate about their paper and their community, but they said they are also struggling to deal with the ubiquitous “newspapers are dead” mantra. Sources, subscribers, and advertisers keep asking them if they will be going out of business soon. They said this was bad for morale. Some seemed to think the newspaper industry crisis was more of an urban issue—the result of big media companies’ flawed business strategies.

Regardless of who’s to blame, rural Canadians have few alternatives if their local paper goes out of business. They are isolated and depend on this one thread to hold them together. Staying positive in an atmosphere of doom and gloom, they told me, thus became essential to their survival in the community, and their survival, some would argue, became an indicator of a community’s health.

While trying to stay positive, however, many worried about the future: who would take over when they died, for example. And in the many towns with declining populations, who would be left to read the paper?

Many had witnessed monumental changes in journalism over the span of their careers; they remembered the “hot lead” days. They saw what was happening today as part of a natural evolution, and had no fear that, in one form or another, the news would survive.

Opportunities

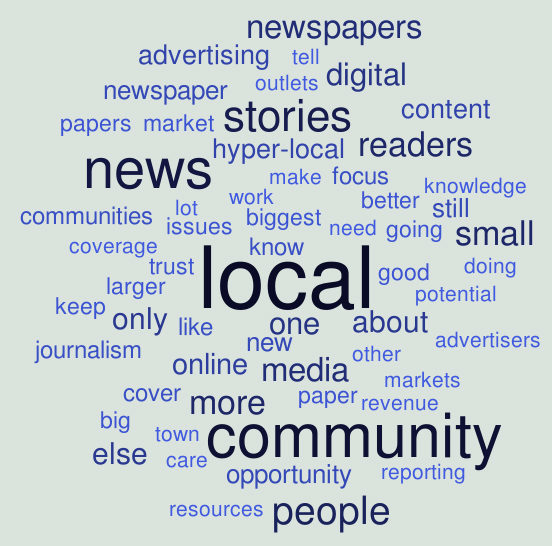

About a third of respondents cited ‘focusing on local’ as the biggest opportunity for small-market newspapers (Figure 32). One respondent explained why this is an advantage: “We are the only ones covering the topics that we cover. Remaining local is key.” Another made the point that “community newspapers are still breaking stories. From the heart-felt community interest stories, to the city council meetings we cover, these small papers are still where news is born.”

Respondents noted that a big part of their advantage stems from small-market newspapers’ position, in many cases, as the only publication covering the issues in the geographical region. “The big provincial and national outlets don’t tend to cover the local issues that our readers care about,” one respondent stated. “So long as those outlets keep ignoring our audience, we remain relevant.” A few participants in the survey noted that the closing of competing publications translates into a potential plus for them in that it left the field open for their publication.

Figure 32. Words mentioned five or more times to describe opportunities